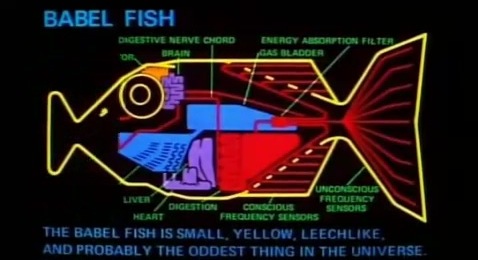

Ideally, shortly after we’ve learned to read we’d all be fitted with a pair of magical (or high-tech) glasses that act as the visual equivalent of Babelfish, and we’d be able to read anything we wanted, no translation required. Alas, we’re not quite there yet, but in the interests of acting as pseudo-Babels, we’ve compiled a list of SFF works from around the world that you can find translated into English. Some of these came from readers suggestions, some of them are Tor.com favorites, and all of them are fantastic. Let us know if we missed any other favorites in the comments!

The Three-Body Problem—Liu Cixin (Chinese)

The award-winning trilogy by Liu Cixin has already sold over 400,000 copies, and helped spark a new wave of science fiction writing in China. Liu says that he “wrote about the worst of all possible universes in Three Body out of hope that we can strive for the best of all possible Earths.” The trilogy uses the “three-body problem” of classical mechanics to ask some terrifying questions about human nature and what lies at the core of civilization. Liu explores the world of the Trisolarans, a race that is forced to adapt to life in a triple star system, on a planet whose gravity, heat, and orbit are in constant flux. Facing utter extinction, the Trisolarans plan to evacuate and conquer the nearest habitable planet, and finally intercept a message—from Earth.

The book’s translator is the multi-award-winning author Ken Liu, whose story “The Paper Menagerie” became the first work of fiction to sweep the Nebula, Hugo, and World Fantasy Awards. The Three-Body Problem will soon be followed by The Dark Forest and Death’s End.

Kalpa Imperial—Angélica Gorodischer (Spanish)

Argentinean writer Angélica Gorodischer has given us over a dozen award-winning novels and short story collections, but this is the first to be translated into English. And you may have heard of the translator… an up-and-coming cult writer named Ursula K. Le Guin.

This book is a macrocosm of interlinked short stories, weaving multiple narrators, oral histories, folk legends, and the rise and fall of empires into a tapestry that celebrates storytelling itself. As Sofia Samatar wrote, Kalpa Imperial’s strength lies in its entanglements, and the way it shows the interconnectedness of beggars and emperors, assassins and lovers, fisherfolk and archivists.

The Master and Margarita—Mikhail Bulgakov (Russian)

Bulgakov’s famous allegorical work pits Satan against a Soviet bureaucracy that refuses to believe in him, while referencing Goethe’s and Gounud’s Fausts.

In 1920’s Moscow, Satan disguises himself as a foreign professor named Woland to do mental battle with Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz (named after Hector Berlioz, who wrote the opera The Damnation of Faust) who believes that Jesus is a completely mythical figure. Meanwhile, in 2nd Century Judea Pontius Pilate and Yeshua are reenacting The Brother Karamazov’s Grand Inquisitor sequence. And wrapped around that is the story of the Master, the author writing about Yeshua and Pontius, whose sanity is saved by his beloved mistress, Margarita. Also, there’s a giant talking cat who loves vodka and guns.

We, The Children of Cats—Tomoyuki Hoshino (Japanese)

This anthology collects and reimagines traditional Japanese folklore, with stories ranging from people growing new body parts at random to haunted forests!

Perhaps the best thing about a book like this is that western readers won’t always recognize the folk story upon which these tales are based, making the premises themselves seem super-fresh and exciting. The characters in the stories are desperate for freedom, from society, from gender, from flesh itself, and in some cases, they even manage to find it. Translator and editor Brian Bergstrom includes an afterword, and the author gives us a preface to introduce us to this wild collection.

Awakening to the Great Sleep War—Gert Jonke (German)

This novel concerns a world in which the fabric of reality itself seems to be slipping away. Flags fall off of their poles and lids no longer fit their containers as Awakening to the Great Sleep War imagines what the smaller problems of a collapsing would truly be like.

Writing an end-of-the-world book that feels relevant and new is a giant challenge for any author, but the multi-award-winning playwright and author Gert Jonke is more than up to the task.

The Star Diaries—Stanislaw Lem (Polish)

Now, this is one you’ve probably heard of! Lem is probably most well-known as the author of Solaris, but it’s often in his more humorous books like The Star Diaries where his talent and originality really shine. The Star Diaries are tales of the voyages of Ijon Tichy, a likeable but hapless explorer, who, among other mistakes, inadvertently created our Universe. Thanks a lot, Ijon.

The stories in the collection often parody sic-fi conventions, and range from cutting satire to slapstick in technique.

The Carpet Makers—Andreas Eschbach (German)

An author of mostly hard SF or thrillers, Andreas Eschbach has been publishing books since 1993. His novel The Carpet Makers is a shockingly intricate series of interconnected stories in which carpets made of human hair become stand-ins for the whole of the universe.

Eschbach himself has a background in software and aerospace engineering, so there’s plenty of actual science embedded in this fantastical tale.

We—Yevgeny Zamyatin (Russian)

Considered to be the granddaddy of dystopian fiction, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We holds the honor of being the first work banned by the new Soviet censorship board after the Bolshevik Revolution. After the 200 Years War wiped out most of Earth’s population, “The One State” rebuilt society as a rigidly controlled collective, and has ruled for a bout a thousand years at the novel’s start.

Considered to be the granddaddy of dystopian fiction, Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We holds the honor of being the first work banned by the new Soviet censorship board after the Bolshevik Revolution. After the 200 Years War wiped out most of Earth’s population, “The One State” rebuilt society as a rigidly controlled collective, and has ruled for a bout a thousand years at the novel’s start.

The Green Wall encircles what’s left of civilization, protecting it from the ruined landscape outside, and all people live in glass-walled apartments, identify by numbers rather than names, and live have every hour of their day according to a mandated schedule called “The Table.” Our narrator, D-503, records his thoughts in a journal as he works on the spaceship Integral, which is being built not to explore the universe, but to conquer other planets. The tone of the journal shifts, however, as he becomes involved with a rebellious woman, I-330, and a group called MEPHI that is plotting to overthrow the One State.

The book was a huge influence on Orwell (and possibly on Huxley as well) and laid much of the groundwork for individuality-hating dystopias to come. It was published in a U.S. translation in 1924, but at a heavy cost: since Zamyatin had the banned book smuggled out, he had to go into exile (actually the author’s third, since he had already been exiled to Siberia twice for being a Bolshevik) and died in poverty in Paris.

The World of the End—Ofir Touché Gafla (Hebrew)

This novel follows a man named Ben searching for his long-lost (and presumed dead) love in an eternal, ethereal afterlife. Deceased spirits of folks like Marilyn Monroe might be here, but finding that one person who you lost in the mortal world becomes the true quest. But when Ben discovers his wife might still be alive in the real world, everything about his existence is turned upside down.

In this novel, being dead is just the start of the story.

The Cardinal’s Blades—Pierre Pevel (French)

Pierre Pevel, winner of the 2002 Grand Prix de l’Imaginaire and the 2005 Prix Imaginales, asked himself an important question: what could make a swashbuckling tale of intrigue set in the time of Cardinal Richelieu even more awesome? The answer to this question, as to so many questions, is DRAGONS.

So we get a 17th Century Paris in which dragonnets are fashionable pets, wyverns are used instead of horses, and the “Blades” of the title are a dragon-mounted team of spies trained to defend France from the schemes of Spain and Italy. The Cardinal’s Blades was followed by two sequels, The Alchemist in the Shadows and The Dragon Arcana, which foreground character development and emotional depth while also delivering tense action. And dragons.

The Witcher Saga—Andrzej Sapkowski (Polish)

If you combine a Philip Marlowe-style antihero with Slavic mythology, and then stir in some mutants, you get The Witcher Saga. Author Andrzej Sapkowski began writing and translating sci-fi while working as a sales rep, and submitted his first story to Fantastyka magazine’s science fiction and fantasy contest on a whim. He came in third (not a bad way to start out), and when the magazine ran the story is became a huge hit!

Sapkowski continued writing about the story’s main character, a mutant hunter named Geralt, in The Witcher Saga. The series’ success allowed Sapkowski to become a full-time author, and has now led to a TV series, a movie, and a video game. English translations of the series begin with The Last Wish, and continues with Blood of Elves (which won a David Gemmell Legend Award in 2009), The Time of Contempt, and Baptism of Fire.

Six Heirs: The Secret of Ji—Pierre Grimbert (French)

In a fantasy world containing magicians, gods, and mortals, telepathic communication with animals doesn’t seem to far-fetched. In this new spin on epic fantasy, Peirre Grimbert tackles a world beset with shadowy thieves and mystical empires.

Citing authors like Jack Vance and Michael Moorcock among his heroes, Grimbert looks to be one big new name to watch in the ever-expanding genre of high fantasy.

Reluctant Voyagers—Elizabeth Vonarburg (French)

Catherine Rhymer thinks she’s losing her mind when Montreal begins…changing. Her search for the truth leads her to a secret revolutionary movement, and then takes her into the North, where she has to confront the creators of her reality.

Author Élisabeth Vonarburg moved from Paris to Quebec, and spent over a decade as the literary director of Solaris, the French-Canadian science fiction journal. Her other works in English translation include The Silent City, Dreams of the Sea, and the The Maerlande Chronicles which won a Philip K. Dick Award in 1992.

Death Sentences—Kawamata Chiaki (Japanese)

When a book opens with an elite police squad hunting down an illicit substance known as “stuff,” your mind probably goes to drugs, or maybe weaponry. But in Death Sentences, “the stuff” is a surrealist poem that kills its readers. It had already claimed Arshile Gorky and Antonin Artaud before causing a rash of suicides in 1980s Japan. Why does it bring death to its readers? Who wrote it? And can it be stopped?

This dizzying mash-up of horror, sci-fi and Parisian surrealism, Kawamata Chiaki’s first novel to be published in English, hops from the Left Bank to Japan to Mars, and turns historical figures including André Breton and Marcel Duchamp into characters in a live-action, and all-too-literal, Exquisite Corpse exercise.

The Shadow of the Wind—Carlos Ruiz Zafón (Spanish)

Shortly after the end of the Spanish Civil War, Daniel Sempre’s father takes him to The Cemetery of Forgotten Books. He is permitted to select a single book, with the warning that he must protect it for the rest of his life. He spends the whole night reading it, but when he tries to find any information on the author, it’s as though the man vanished. What happened to Julián Carax? And who is the mysterious stranger who is destroying all of his works?

This surreal labyrinth of a book gives us a satire of Franco’s regime, a terrifying mystery, and a tragic romance rapped up in a story of the importance of literature.

If you’ve read some genre fiction which was originally written in a language other than English, we want to hear about it! Read something that hasn’t been translated, but you think is amazing? We want to hear about that too!

I recommend: Cold Skind from Albert Sanchez Piñol

A really good story, the original is in catalan.

If you have a another Russian novel, I think it should be Arkady & Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic.

There’s quite a bit of good Japanese SF, including that from Haikasoru: thus far I’ve read and enjoyed Hiroshi Sakurazaka’s All You Need Is Kill and I have Issui Ogawa’s The Next Continent on the to-read pile.

I’m rather interested in The Carpet Makers and hope to get round to it soon.

Wonderful, thank you for bringing these to everyone’s attention.

In 1920’s Moscow, Satan disguises himself as a foreign professor named Woland to do mental battle with Mikhail Alexandrovich Berlioz (named after Hector Berlioz, who wrote the opera The Damnation of Faust) who believes that Jesus is a completely mythical figure.[/i]

Whoa, I don’t know who wrote that as the book’s plot summary, but Berlioz dies in the very first chapter, so most of The Master And Margarita is emphatically NOT about him.

@SchuylerH: I recently (within the past few years) read a newer translation of Roadside Picnic. I second your recommendation.

Did anybody else see parallels between Satan in Master and Margarita and the thistle-haired man in Jonathan Strange? Not to say the latter was Satan, that is.

The Neverending Story by Michael Ende. Classic and wonderful.

I added translations to my rotating reviews themes in the summer but I only have a dozen so far….

(Translation Wednesday is skewing male so very open to suggestions re: translated works by women)

http://jamesdavisnicoll.com/reviews/series/translation-wednesday

To whomever suggested The Neverending Story, ALL THE YES!

Also:

Sergei Lukyanenko’s Night Watch series

Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino

Stories of Ibis by Hiroshi Yamamoto

Ten Billion Days and A Hundred Billion Nights by Ryu Mitsuse

Dragon Sword and Wind Child by Noriko Ogiwara

@6: Hmm, I’m blanking somewhat on newer writers. There’s Thea von Harbou’s Metropolis and The Rocket to the Moon which were, I think, rather influential (at least in the film versions) but I’m not really sure if that’s the kind of thing you’re looking for.

On Tor, Mahvesh Murad took a look at the early Sultana’s Dream by Roquia Sakhawat Hussain. Might it be worth a look?

In Soviet SF, there’s Valentina Zhuravlyova, several of whose stories appeared in Ballad of the Stars, along with those of her husband, Genrikh Altov. I’m afraid I haven’t read it though.

From Japan, there is Kaoru Kurimoto’s Guin Saga but I suspect that’s rather longer than you would like.

Though not considered SFF, “Smilla’s Sense of Snow”, a murder mystery by Peter Hoeg, takes an unexpected fantastic turn at its end.

When it comes to Sapkowski, my Polish wife prefers The Hussite Trilogy, which has never been translated, unfortunately.

I loved The Scar by Sergey and Marina Dyachenko. It’s an excellent fantasy with elements of psychological horror. I need to see if any of their other books have been translated to English.

I’d suggest everythingfrom the Strugatsky brothers (Russia) (and am shocked that not even Roadside Picnic made this list)

Blindness by Jose Saramago (Portugal) isn’t often considered sci-fi, but it is practically a retelling of John Wyndham’s Day of the Triffids minus the carniverous plants

And seriously, why no Jules Verne (France)?

I can’t believe you didn’t mention anything by the Strugatsky brothers.

After reading this list I realized one of the best fantasy novelists has not been transated in english. I strongly reccomend Valerio Evangelisti, whose Eymerich saga turns the life and deeds of the imfamous inquisitor into the starting point of a millennium long fight against mutants, deseases, psi powers and the degeneration of the human race.

Two comments:

1. If you’re going to pick a Lem, why not The Cyberiad? Best thing he ever wrote.

2. WTF? No Hiroki Murakami? Try 1Q84.

@@@@@ 7. AMR: I second your all the yes to Neverending story and add ALL THE YES to Italo Calvino’s Cosmicomics!

@@@@@ 10. Walker: I’ve read both and still like the Witcher more. The Hussite Trilogy is sort of better crafted, more thought through, more classicly-literary, plus set in real-world history with historical events described with wonderfull precision, and it is simply awesome.

But Witcher saga has this “something” I don’t know how to describe, and that “something” makes it one of my favorite books ever.

If we’re talking about untranslated books as well, I add to the list sci-fi by the Dutch author Tonke Dragt; in original i’ts called Torenhoog en mijlen breed. It takes place in future on planet Venus, which has some really fantastic (and dangerous) forests on it; and I love that book. By some freak coincidence it’s translated only to three other languages, czech being one of them.

And I’m not sure at all if Czech author Julius Zeyer has ever been translated to english; he is not known as a fantasy author, but I think he was, and one of the first ones, if not the very first; especially because of his novel “Romance of the faithful friendship of Amis and Amil”.

Oh and I must mention Karel Capek’s R.U.R – because, seriously, how many sci-fi theatre plays do you know?

I also recommend Michal Ajvaz; he writes very unusual fantasy and I know for sure at least two of his books, The Other city and Golden Age, are translated to english.